Reinhardt Domains Examples and Counter Examples

Introduction

In the realm of complex analysis, the study of domains within complex spaces is fundamental to understanding the behavior of holomorphic functions. Complex numbers, which can be represented geometrically as points on a plane, extend naturally into higher dimensions as complex vectors in $ \mathbb{C}^n $. This geometric perspective allows for the exploration of intricate structures and symmetries within these spaces.

One particularly interesting type of domain is the Reinhardt domain. Reinhardt domains exhibit specific rotational symmetries that make them a focal point in the study of several complex variables. Understanding these domains not only sheds light on fundamental concepts in complex analysis but also has implications for areas such as function theory and mathematical physics.

What are Reinhardt Domains?

A Reinhardt domain in $ \mathbb{C}^n $ is a domain $D$ with a particular invariance property under coordinate-wise rotations. Formally, a domain $ D \subseteq \mathbb{C}^n $ is called a Reinhardt domain if for every point $ (z_1, z_2, \dots, z_n) \in D $ and for all real numbers $\theta_1, \theta_2, \dots, \theta_n$, the point obtained by rotating each coordinate individually also lies in $D$:

$$ (e^{i\theta_1}z_1, e^{i\theta_2}z_2, \dots, e^{i\theta_n}z_n) \in D $$

This means that $D$ is invariant under the action of the torus $ (\mathbb{S}^1)^n $, where $ \mathbb{S}^1$ represents the unit circle in the complex plane.

Geometric Intuition

To grasp the geometric intuition behind Reinhardt domains, consider the complex plane $ \mathbb{C} $. Rotating a point $z$ around the origin corresponds to multiplying it by a unit complex number $ e^{i\theta} $. In $ \mathbb{C}^n $, we can rotate each coordinate $ z_j $ independently by angles $\theta_j$.

A Reinhardt domain remains unchanged under such independent rotations. This property is akin to the domain being “circular” in each coordinate direction. Visualizing this in $ \mathbb{C}^2 $, a Reinhardt domain would look like a shape that, if spun around each axis, would remain within the same domain.

Examples of Reinhardt Domains

Polydiscs

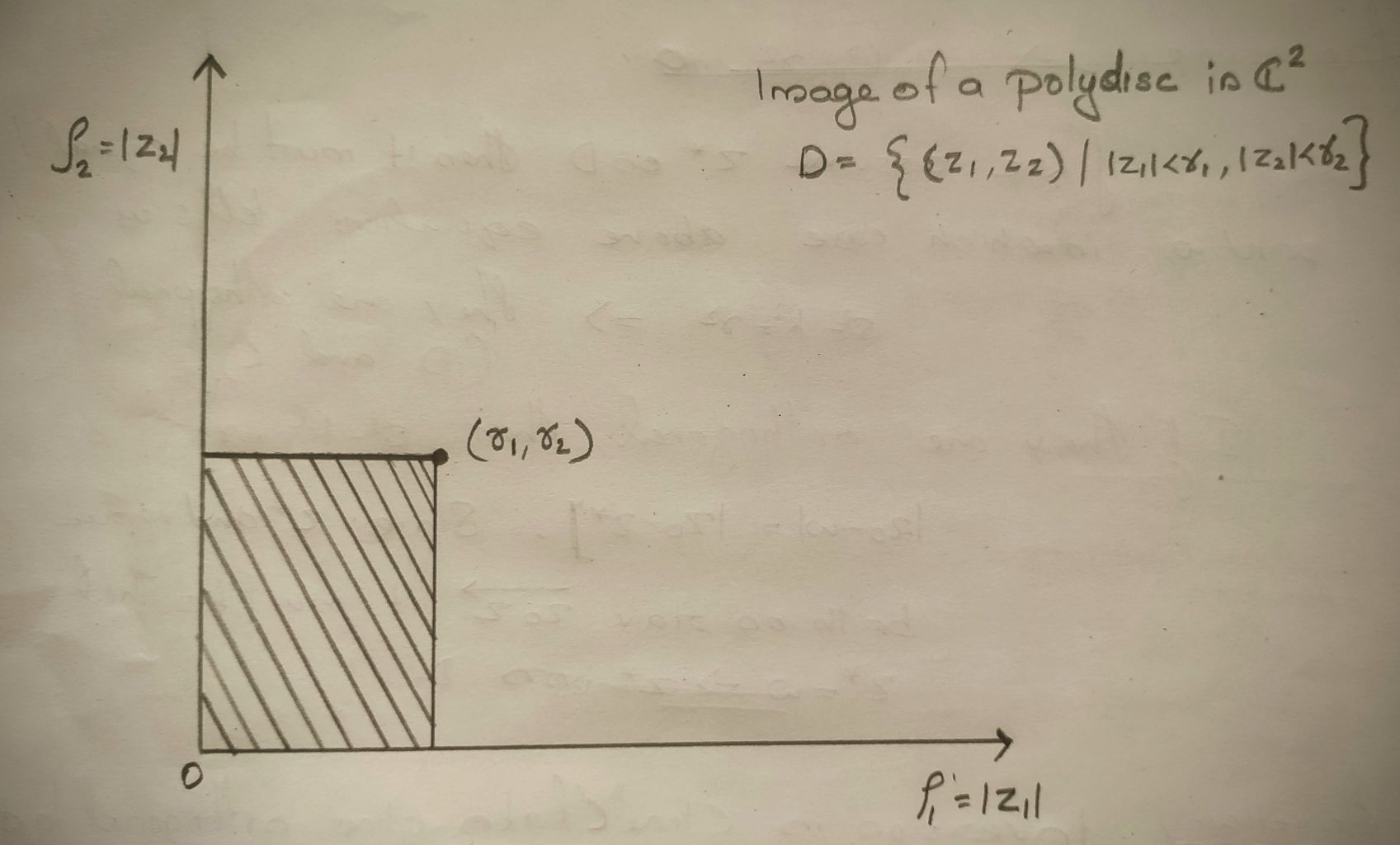

A simple example of a Reinhardt domain is the polydisc in $ \mathbb{C}^n $:

$$ D = \left\{ (z_1, z_2, \dots, z_n) \in \mathbb{C}^n \mid |z_j| < r_j \text{ for } j = 1, 2, \dots, n \right\} $$

Each $D_j = \{ z_j \in \mathbb{C} \mid |z_j| < r_j \} $ is a disc in $ \mathbb{C} $. Since the modulus $ |z_j| $ remains unchanged under rotations $e^{i\theta_j}z_j $, the polydisc is invariant under coordinate-wise rotations, making it a Reinhardt domain.

Complex Balls

Another important example is the complex ball (or unit ball) in $\mathbb{C}^n $:

$$ B = \left\{ (z_1, z_2, \dots, z_n) \in \mathbb{C}^n \mid \sum_{j=1}^{n} |z_j|^2 < 1 \right\} $$

The condition $\sum_{j=1}^{n} |z_j|^2 < 1 $involves the moduli $ |z_j| $, which are unchanged under rotations. Therefore, the complex ball is invariant under coordinate-wise rotations and is a Reinhardt domain.

Other Examples

- Hartogs Domain: Domains of the form $ D = \left\{ (z_1, z_2) \in \mathbb{C}^2 \mid |z_1| < \phi(|z_2|) \right\} $, where $ \phi $ is a positive function, are Reinhardt domains if $\phi $ depends only on $|z_2|$.

- Products of Reinhardt Domains: The product of Reinhardt domains in lower dimensions is also a Reinhardt domain.

Absolute Space

The notion of absolute space is instrumental in analyzing Reinhardt domains. Absolute space refers to considering only the moduli (absolute values) of the coordinates, effectively “flattening” the domain onto $[0, \infty)^n$.

By mapping:

$$ (z_1, z_2, \dots, z_n) \mapsto (\rho_1, \rho_2, \dots, \rho_n) \quad \text{where} \quad \rho_j = |z_j| $$

we consider the image of $D$ under this mapping. Since Reinhardt domains are invariant under rotations, their structure is entirely determined by the behavior of $ |z_j| $.

Logarithmic Convexity

An important property related to absolute space is logarithmic convexity. A Reinhardt domain $D$ is logarithmically convex if the set:

$$ \left\{ (\log |z_1|, \log |z_2|, \dots, \log |z_n|) \mid (z_1, z_2, \dots, z_n) \in D \right\} $$

is a convex subset of $ \mathbb{R}^n $.

This property is significant because it relates to the domain of convergence for power series in several complex variables. Logarithmic convexity ensures that power series expansions have a well-defined convergence behavior within the domain.

Counterexamples

Understanding Reinhardt domains is further enriched by examining domains that are not Reinhardt domains.

Non-Reinhardt Domains

- Elliptic Domain:

$$ D = \left\{ (z_1, z_2) \in \mathbb{C}^2 \mid |z_1| + |z_2| < 1 \right\} $$

This domain is not invariant under independent rotations of $z_1 $ and $ z_2 $, as the sum $ |z_1| + |z_2| $ could change.

- Sector Domain:

$$ D = \left\{ z \in \mathbb{C} \mid 0 < \arg(z) < \frac{\pi}{2} \right\} $$

Rotating $ z $ may take it outside of $D$, so this domain is not a Reinhardt domain.

Why They Fail to be Reinhardt Domains

These domains fail to satisfy the definition because they lack invariance under coordinate-wise rotations. In the elliptic domain, rotating one coordinate could increase $ |z_j| $, violating the condition $ |z_1| + |z_2| < 1 $. In the sector domain, rotating $z$ changes its argument $ \arg(z) $, potentially moving it outside the specified range.

These counterexamples underscore the importance of the rotational invariance property in defining Reinhardt domains.

Further Reading

Convexity and Pseudoconvexity | Tasty Bits of Several Complex Variables